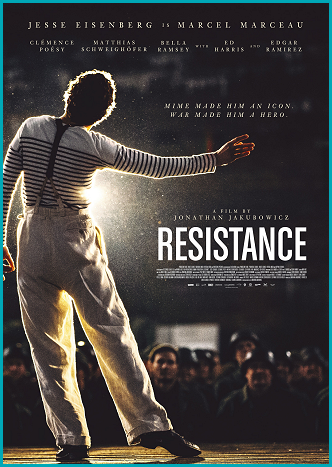

From Silent Stage to Silver Screen: Bringing Marcel Marceau’s Mime to Resistance

By Jesse Eisenberg and Lorin Eric Salm

Dramatizing the story of the young Marcel Marceau and bringing it to life in the feature film Resistance was, as in all films, the result of a collaboration of the many people involved in the filmmaking process. This article focuses narrowly on the work that Jesse Eisenberg and Mime Choreographer and Coach Lorin Eric Salm did together during Eisenberg’s preparation to play the lead role of Marceau. Each one offers his own perspective on the process in turn.

◊ ◊ ◊

Jesse Eisenberg:

For the most part, movies are about two kinds of characters: an everyman struggling against larger forces or a great man doing something superhuman. And when a movie features a character who is skilled in a particular area, they tend to be “the best” in their field. Do you remember seeing the movie about the sixth man on the basketball team who consistently averaged 10 points a game? Do you remember the great war epic about the mid-level lieutenant? Or the guy who set out to take down wall street and ended up making a decent living and moving to a split level? These are not movie characters. These are characters who go to the movies to escape their ‘everyman’ lives.

Movies are about the greatest magician, the youngest billionaire, the world’s best mime. In fact, I’ve played all three of those characters. And it is all too common for actors to play roles for which they are completely under-prepared. Of course, this is also one of the joys of the profession – to be able to learn a new skill and meet the best in the field to learn how to appear credible.

Movies are about the greatest magician, the youngest billionaire, the world’s best mime. In fact, I’ve played all three of those characters. And it is all too common for actors to play roles for which they are completely under-prepared. Of course, this is also one of the joys of the profession – to be able to learn a new skill and meet the best in the field to learn how to appear credible.

I’ve worked with some of the best magicians, the best computer hackers, the best stunt fighters and now, the best mimes. And my lessons usually have the same trajectory: I begin the process eager to learn, become overwhelmed by something I can’t do, grow frustrated with myself and the skill I’m supposed to be mastering and finish the project wishing I had more time to prepare.

The process of learning mime for Resistance was a bit different for a few reasons. Most notably, I had a lot of time. Lorin Eric Salm, who was the brilliant choreographer and my teacher for the movie, began working with me several months prior to filming. It allowed me to overcome my usual growing pains over the course of six months of rehearsal rather than midway through a film shoot. The other difference between working on mime as opposed to those other skillsets is that mime is so closely related to what I love about acting. The style of mime that I like – that Marceau performed and that Lorin studied – is about telling a story. It is rich with character and humor and pathos. Of course, there are elements that are strictly physical and require practice and dexterity, but being engaged with the story you are telling is the primary goal.

Over the course of six months, I learned Lorin’s choreography and became increasingly good at ‘telling the story.’ The more comfortable I got with the physical demands of the routines, the more I was able

to immerse myself in the emotion of the pieces. It got to the point where I would feel the emotion of a mimed character as much as I would feel for a non-mimed character.

One of the interesting things that Lorin told me about Marceau is that he would perform certain gestures “incorrectly.” By way of example, Marceau would do an elegant hand flourish but his ring and pinkie finger would be spread apart, rather than flush together. If a student of Marceau’s would copy this, Marceau would correct the student. My takeaway from this is twofold: One, mime, like any art form is meant to be personalized and two, you have to learn the rules of a craft before you can break them. It was important for Marceau’s students to learn the perfect formations before they could begin to make it their own.

In a kind of meta way, I was learning Lorin’s version of Marceau but had to make it my own. In this way, I thought about what Marceau would have been like as a young performer, prior to becoming the success that we all know. I thought about what I was like when I was starting out as an actor – that young mix of arrogance and joy that slowly recede as you become more proficient. In this way, I performed Marceau as alternatively resentful when he wasn’t feeling appreciated and jubilant when he was performing in his element. And since I was relatively new to the craft of mime, Marceau’s excitement bled into my own.

The trick of playing a real person in a movie is to find a way to make the role your own without ignoring what the audience knows of that person. The actor who appears authentically alive will convince the audience far more than the actor who strives for an authentic facsimile. In my experience, audiences are far more forgiving of inaccuracies than they are with an inauthentic performance. This is what I have striven for anytime I was playing a real person. And so, even in the case of Marcel Marceau – a French born man hiding from the terrors of World War II – I felt a strong personal overlap.

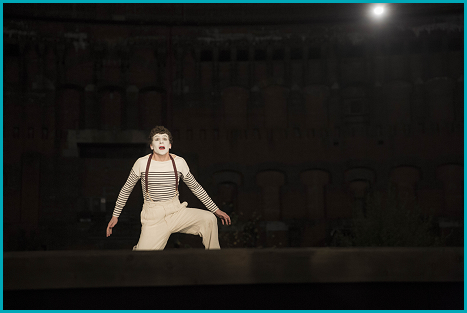

By the time we were filming the finale, where Marceau is in full makeup and performing for 5,000 troops in Nuremberg, I had the amazing sensation that the performance was all mine. Of course, it was not just mine. It was Lorin’s choreography, which was inspired by Marceau’s performance style and contextualized by writer/director Jonathan Jakubowicz’s emotional screenplay. But like any good performance, I had found a way to own it, to learn the rules in order to break some and ‘tell the story.’

◊ ◊ ◊

Lorin Eric Salm:

In writing an account of my work on Resistance, I would like to appeal not only to film enthusiasts interested in background on the film in general, but also to those that are familiar with Marcel Marceau’s work, and in some cases to those that are mime actors, mime teachers, and mime students themselves. I’ve divided my comments into reflecting on the training period and explaining the basis of the mime choreography I created for the film.

Training

In my eighteen years as a mime and movement coach in film and television, it has been my experience that directors, producers, and casting directors usually underestimate the difficulty of their actors learning to mime even technically well after some brief amount of coaching, but that seems to be what most expect when they cast an actor with little mime experience (or most often, no mime experience) and then decide to bring in a mime coach. Fortunately, this was a production that recognized the challenge in training an actor not only to perform mime, but to do so well enough to give the impression of seeing a young man who would later become the world’s most famous mime performer. Director Jonathan Jakubowicz and producer Claudine Jakubowicz had enough respect for mime to realize that Jesse – an actor with no previous mime training or experience – would not be able to master the art form in the period between casting and shooting the film. They allowed for potentially months of training for Jesse to achieve the highest level of skill possible in the time available.

While Jesse had no previous mime training, though, he did not come to this challenge with none of the skills necessary for mime. A mime performer is not only a mover, but an actor. Mime requires mastery of movement on a technical level, but that technique must be coupled with strong acting skills, or it can remain a demonstration of physical virtuosity, and fall short of creating a moving, dramatic performance. (Here I use the term “dramatic” to mean both drama and comedy.) Jesse, an Academy Award nominee, had already proven to be a very talented actor, so this was extremely helpful. Mime, however, requires a different style of acting, so part of my work with him was to acquaint him with the less realistic, more stylized type of acting used in mime.

Fortunately, almost the whole film takes place during the period before Marceau had any mime training. We felt this gave us license to have him perform mime with less than the great skill and experience shown in his professional work in later years. We wanted to show his innate talent for movement and character, and the influence of silent films he had watched since he was a young child. Marceau, though, didn’t formally study mime until after the war, when he became a student of Etienne Decroux. For most of the period in which the story takes place, he wouldn’t even have seen the now-classic French film Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise), which was released in 1945, and which helped reintroduce the French public to the art of mime. The young Marcel’s talent hadn’t yet been fully formed by the technique that he later learned from Decroux.

This helped with training Jesse. His skills didn’t have to match those that Marceau achieved after he had been trained in mime. Still, Jesse needed to be skilled enough for the viewer to believe that he was a younger version of the very talented Marceau. His skills also had to be good enough for his miming to move the viewer as powerfully as Marceau’s real-life work did, otherwise the mime in the film would not serve its dramatic purpose.

Jonathan had related to me Jesse’s preference to begin with choreography rather than beginning with the basics as if he was embarking on a full training course in mime. We jumped right in, then, with one of the comic scenes. This gave Jesse the opportunity to see right away where we were going with his training, and it gave me the opportunity to see where we were starting from, by assessing his movement ability and his sense for this new style of acting. It was no surprise to either of us to find that we had our work cut out for us. I don’t say this as a criticism. I’ve coached many artists who are experts in their particular styles of performance – whether actors, comics, dancers, circus artists, magicians, or others – and to put it simply, those that have never done mime . . . have never done mime. Even those who specialize in a very physical performance art are not immediately adept at mime. Mime requires using some skills that are shared by these other arts, but also requires others that are unique to it.

One of Jesse’s strengths, and one that contributed greatly to the success of our process, was the humility with which he approached the work. A star actor who requires training in an entirely separate skill like martial arts or horseback riding, for example, could approach the task without any insecurity. If the skill is entirely new to them, they have no current level of skill to feel judged about, and they have no reason to feel threatened by the skill of the coach, or to be resistant to the idea that they need to learn something new for their role. As I mentioned before, however, mime is acting, and while it is a different style of acting than that of film acting, it could make a very skilled actor feel unduly challenged. Jesse was secure enough in his expertise as an actor not to feel threatened by our work together, as he recognized that my job was not to help him improve on the acting skills he already had, but to help him adapt them in a new way.

During our first week of training sessions, I acquainted him with all the mime choreography in the film, from the longest performance scenes to the smallest bits of mime that appeared in other scenes. It was through the process of teaching him the choreography that I was able to gradually introduce him to the various physical skills and dramatic concepts needed for him to perform the choreography as intended.

After this initial, intense week of training sessions, it was time for Jesse to work on his own for a little while to further memorize the choreography, and to practice both that and the physical skills that were new to him. We would meet again about a month later to continue, and then, after a two-month break, we met for one final group of sessions.

As Jesse became comfortable with the choreography and the stylized way of acting in mime, and as he improved in his performance and gained confidence in his mime work, he was able to not only perform the mime scenes according to the exactness of what I had created, he was then able to incorporate his own strengths as an actor into his interpretation. As I’ll speak more about in a moment, there were reasons why the styles of mime acting and film acting had to be combined for this role, and that’s where Jesse’s sensibilities about how to play certain moments informed his final performance.

The time that we spent together afforded us the opportunity both to focus on the physical work and to discuss other aspects of Marceau as a performer and as a person. Jesse is a naturally curious person, and likes to ask many questions in his enthusiastic desire to learn and to understand. I’m equally enthusiastic about sharing my passion for mime, and for talking about Marceau in terms of everything I’ve learned about him and from him. I gave Jesse my personal impressions of a man I knew in his sixties and seventies who Jesse was going to have to play as a teenager. I hoped that by knowing what kind of person and artist Marceau had become, Jesse might be able to better imagine the young man he started out as. I shared with him everything from what Marceau was like as a teacher to how he behaved in casual conversation over dinner. I also tried to relay to Jesse the connections between the events in Marceau’s real life and the influence those events had on the mime work he created. Jesse seems to be sensitive both in life and in acting, and I felt that allowed him to genuinely understand the importance of Marceau’s own sensitivity to who Marceau was, both on stage and off.

Choreography

The choreography for Resistance really began with Jonathan Jakubowicz. As both writer and director, the choreography he asked me to create had to serve a purpose in the story and had to work with his vision for the film. Jonathan wrote scenes for mime pieces, and in some places, a basic idea of the mime piece in the scene. I choreographed the pieces based on his script, and then modified the choreography with his direction in order to fulfill that vision. He relied heavily on me, however, and my knowledge of Marceau’s work, to further develop his ideas and to stage them, and in some scenes, to suggest the whole direction of the mime pieces.

Before I began work on the choreography, we both agreed on certain principles that would guide our approach. We felt we had to allude to the great mime artist Marceau would become by putting hints of his later work in the mime scenes in the film. We used certain scenes in the film as fictional hypotheticals, taking artistic license to suggest circumstances in which Marceau might have spontaneously mimed something that would remind the audience of Marceau’s real-life creations. We intentionally avoided using any of his actual pieces or exact choreography. Instead, I created original choreography using the fundamental techniques that would later become the basis for his work and using characteristic movements that would come to define his style. Rather than portraying Marceau’s mime work in the film exactly as audiences remember seeing him on stage, my intention was that the audience would be able to see in this young version of Marceau the seeds of the great artist of the future.

Unlike in Marceau’s stage work, the mime pieces in the film were not stand-alone performances that could be created for their own sake. Each one had a dramatic purpose in the film related to the plot, so I had to take that into consideration in creating the choreography. This influenced the theme and duration of each piece, and aspects of the movements in each one, such as their size, shape, tempo, and dynamics. While there are two scenes in which Marcel performs rehearsed mime pieces on stage for audiences, the rest of the mime in the film was meant to look spontaneous, so this also influenced our choices. Since these “spontaneous” moments of mime had specific dramatic purposes to fulfill, it was also necessary, as I mentioned earlier, to combine to some extent the styles of film acting and of mime acting. I had to keep in mind that even the stage performance scenes were intended to be performed on camera, and not truly on stage, so I made certain choices based on that, while still aiming to give the impression of a stage performance. (It’s worth noting that when the real Marceau had his mime works filmed or videotaped, he would sometimes restage certain elements to account for the camera and for editing. He usually didn’t attempt to simply duplicate his stage performance for the camera exactly as he would have performed it for a live audience.)

More specifically, viewers who are familiar with Marceau’s work will recognize moments that I meant to be reminiscent of his creations like The Hands, Walking Against the Wind, and Bip as a Soldier. In other scenes, I incorporated what Marceau called retournée de personnage, or turn of character, to show his remarkable ability to portray multiple characters in a single scene, and to quickly change between them. Chaplin’s influence is quite apparent in the cabaret scene, though here my aim was not to have Jesse imitate Chaplin, but rather to have him play Marceau imitating Chaplin.

Marcel Marceau’s intention, when teaching his students mime, was never to create little Marceaus, or a new generation of Bips. (Bip was his famous everyman character.) He imparted to us the physical techniques, the style of acting, and the dramatic principles that are essential to strong mime creation and performance. While part of learning from him was learning to be able to do things exactly as he showed them, his intention was never for us to copy him exactly when creating our own work, and he assumed that once we became professionals, we would acquire our own styles, and would make choices based on our own influences and artistic instincts. His teaching could remain the foundation for our work without dictating it.

I not only became a professional mime actor, creating pieces in my own way, but I’ve also taught Marceau’s technique to my own students. In the years that I’ve been doing so, I’ve made it my mission to teach his technique faithfully, and not to change it. While I created some of my own methods for teaching or explaining certain techniques or concepts (without changing them), I teach much of it just as he taught it to me. Nevertheless, I am my own artist, and have developed a style of my own in my creation and performance. When creating the choreography for Resistance, and when teaching Jesse to perform it, I took stock of the fact that unlike in my other mime coaching or creation, this time my goal was to mimic Marceau! Part of my work on the choreography was to think like Marceau again, and to move like Marceau again. My job was to create new choreography, but to make it look like Marceau had created it, and in creating and teaching the movements, I had to take care not to let my own style come through. It was not enough this time to use Marceau’s work as a basis for mine; I had to use his personal style, even specific idiosyncrasies that appear in his movements. Just as Marceau was a stickler for the smallest detail, I knew that my attention to these details would help give authenticity to Jesse’s portrayal.